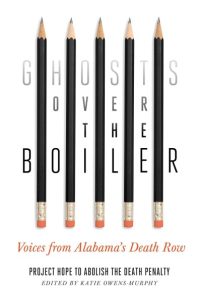

Ghosts Over the Boiler: Voices from Alabama’s Death Row

Author: Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty; Katie Owens Murphy (editor)

Author: Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty; Katie Owens Murphy (editor)

Publisher: Vanderbilt University Press, 2023. 344 pages.

Reviewer: Elizabeth Vartkessian | September 2024

Ask a person to describe an individual living on death row in the United States and a common response is that the person is evil, simply a murderer, or somehow extraordinarily different to the rest of society. As a mitigation specialist who investigates the histories of people facing sentences of death or other severe punishments, I spend significant time interviewing people who have known my client, his family, or the community in which he was raised and some version of that response is typical. Within our culture there is an instantaneous association between viewing a person on death row as one thing, typically the act for which they are accused or convicted.

Keeping the full picture of a person who has been convicted of murder away from society is essential to maintaining the narrative that there is something uniquely different about someone who has been sentenced to death. In my work, I spend thousands of hours unearthing the life history of a client. Through that painstaking work, I glimpse the full picture of development, experiences, and potential of a person who has killed. The act of learning about the uniquely human experiences – friendships, curiosities, heartache, loss, creativity, joy – causes the singular view of my clients to fade away. In its place is the more complicated truth that a person can cause great harm and still have the capacity to grow, change, and redeem. That there is always the potential for humanity to flourish even in the harshest places.

Ghosts Over the Boiler provides another opportunity to glimpse the utter humanness of the contributors. The book is an edited volume of writings from condemned men living on Alabama’s death row and who comprise the organization, Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty. Project Hope is run by the death-sentenced inmates who solicit contributions from other death sentenced people in Alabama, author the works, format and produce a quarterly newsletter entitled On the Wings of Hope, which is distributed to their supporters. As Brian Baldwin one of the men who comprise Project Hope writes, “We ask you to see them as writers, not as people of fault…we hope to show that inmates on death row have the ability to think, make decisions, and care about other people”. Pg 43.

The book begins with an Introduction by the Katie Owens-Murphy, the editor of the volume who became acquainted with Project Hope through one of its only surviving members, Gary Drinkard, the 93rd death row exoneree whose own experiences of wrongful conviction are also documented in the book. Though Mr. Drinkard was exonerated in 2001, he continues the work of Project Hope as a free person advocating for the end of capital punishment. Owens-Murphy’s introduction also provides a historical sketch of the founding of Project Hope and the aim of the contributors to both provide support and hope to each other through writing. Thoughtfully contained in the Introduction are images of the original writings and photographs of the men, who have almost all been killed by Alabama, which serves as a reminder of the people who are the heart of this work – people who are nearly now all deceased that the reader has a chance to get to know through their works.

Details about the crimes for which they have been convicted are largely absent both in the introduction and throughout the volume, which forces the reader to hold each man in their minds as a person first. When some information about the actions that have led the men to death row are given, it is given in expressions of remorse, the suffering and abandonment experienced as a youth, or the myriad other life circumstances that failed to provide healthy developmental opportunities. Though not the purpose of the book, it is helpful to see mentions of the ways in which trauma, neglect, mental illness, and other experiences play a role in how harm occurs. As a reader, this is one area where more could have been shared about the common experiences that may have led people to behave in harmful ways without detracting from the overall aim of the book to connect the public to the men on Alabama’s death row.

After the Introduction, an interview between Owens-Murphy and Project Hope’s Jeffery Lee, Randy Lewis, and Anthony Boyd provides another opportunity to understand the history of the organization and the themes that are often raised in the contributions to the quarterly newsletter, On the Wings of Hope. As happens throughout the book, the interview highlights the tension at the heart of the death penalty, the complexity and utter normalness of the men who are going to be killed and the ways in which they continue to seek positive experiences as they await execution. It is also a reminder of how unique of a group this is – Project Hope is a non-profit organization where all the members will eventually be killed. The members memorialize who they are individually and the toll executions take on the organization.

The rest of the book is separated into five parts chronologically ordered, which span the 30-year history of Project Hope and the works of the men, which have appeared in the newsletter.

Part I, entitled the Beginnings is a collection of writings that highlight the early days of living on death row, the ways in which the men look out for each other, their rituals and routines. For instance, when someone new arrives to Holman Prison, the site of Alabama’s death row, they are given a welcome package with toiletries and food to hold them over until they are able to order items from the prison store. It is a kindhearted gesture of community which many people unfamiliar with people living on death row might be surprised to learn about. The section also includes contributions that remind the reader of practices that are no longer permitted, such executing youth under the age of 18. That practice was outlawed by the Supreme Court outlawed it in 2004.

Themes of human connection, friendship, loss, and love appear throughout the second section, Will You Hear Me Now? An essay about the death of a friend by Carey Grayson provides a good illustration,

“Real friends are the people who see you for what you are, know you for who you are. They know your secrets and refuse to use them against you. They tell you in no uncertain terms when you’re being an ass, and defend your stupidities to the world while naming you an idiot to your face. They are the ones that accept your flaws as readily as your assets. Sebo was my friend and all who know me know that I choose those whom I attach carefully. There is no secret I would not trust him with, no help I would not offer him. He was my best friend and I miss him more than I can say” pg 134. Anyone who reads this will know what it feels like to have such a friendship and can imagine the pain experienced at the loss of someone so special.

Section three entitled, The Killing Machine, details the men’s experiences of how eager and committed Alabama is to execution. It opens with news of recent deaths, both those effectuated by the state through execution, but also deaths that have been caused by disease. Living on death row causes a person to deteriorate – inmates are sedentary, aging, and often have complex medical and mental health conditions that shorten their lives.

A short and poignant contribution entitled, Out to Pasture by James Largin is an effective reminder of how death is ever present in the daily lives of the contributors. “They can dress it up anyway they want to, but they murder us in there. It’s very cold and calculated. They are all business when it comes to the slaughter house.” P 171.

The last two parts of the book, Part IV, entitled It’s the Southern Way and Part V, Botched Rulings and Botched Executions, focus on the retributiveness that drives the system in Alabama and beyond. Contributions provide details about the commitment of officials within the state to carry out executions, such as a prison warden filling prescriptions in their own names to obtain lethal drugs. Though the last two parts are split, the two sections really go hand-in-hand as both trace legal developments nationally and in the state that impacted the application of the death penalty. Authors discuss the confirmation of a new Supreme Court justice, Neil Gorsuch, the Arkansas Effect, which was to try and kill as many men in a two-week period due to soon expiring drugs, and the struggles of the Alabama Department of Corrections to get executions done successfully. The last contribution is a poem written by Nathanial Woods, who was executed though there was strong evidence that he was likely innocent.

A short Epilogue completes the volume with a commitment by the members of Project Hope to continuing to lift up the voices of the condemned in an effort to see the total abolition of the death penalty.

The book is successful in drawing out a core thread, which is that those on death row have more in common than different than one might think between the condemned and everyone else. Project Hope contributor Bart Johnson points to the fact that, “There’s healing that needs to go all around” pg. 28.

The contributors believe that writing is a form of connecting to the public, raising the voices of people impacted by the death penalty, and providing little-known facts about capital punishment in the hope that sharing the information will enable people to make more informed judgements. In this regard the book is also successful.

In addition to the humanity that pours forward from the pages is a clear alignment between the things these men write about from 1990 to 2020 – thirty years – and how that mirrors the national conversations around punishment, current affairs, elections, and judicial appointments. It is a history of a group, of the human spirit and the human condition. Though I have connected with many people facing the death penalty, this is intimate, connective, and essential reading for any person interested in interrogating the purpose of capital punishment.

Elizabeth Vartkessian, Ph.D. is the Founding Executive Director of Advancing Real Change (ARC), Inc. a non-profit that creates a more just world by promoting empathy, dignity, and equity within and beyond the criminal legal system.